Let’s start by offering up the interesting back matter found on current copies of The Lorax:

“UNLESS someone like you,

cares a whole awful lot,

nothing is going to get better.

It’s not.—The Lorax

Nearly forty years ago, when Random House first published Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax, it sent forth a clarion call—to the industry and consumers alike—to conserve the earth’s precious and finite natural resource. The message of it’s whimsical yet powerful tale resonates today more profoundly than ever. In every corner of the world we are at risk of losing real-life Brown Bar-ba-loots, Swomee-Swans, Humming-Fish, Truffula Trees, and the forests they inhabit.

Together, Dr. Seuss Enterprises and Random House proudly sponsor The Lorax Project, an ongoing multifaceted initiative designed to raise awareness of environmental issues and inpsire earth-friendly action worldwide by passionate individuals of all ages.

Dr. Seuss Enterprises and Random House support conservation groups around the world to enhance critical activities needed to protect the real-life Lorax forests, whose preservation is essential to all life on our planet” (Seuss, The Lorax).

The front cover of newer copies of The Lorax also comes stamped with “earth-friendly, printed on recycled paper” (Seuss, The Lorax).

Before even opening the book, readers are given explicit indication of the political implications of the text.

As a researcher of children’s picturebooks, my original motivation to for endeavoring into the genre was an inexplicable interest in the text and images of Dr. Seuss.

The Lorax is a valuable example for someone interested in the interplay of text and images because it achieves and incredible Using the political lens provided by this week’s secondary texts, let’s delve into the work that is being done in the wordplay as well as the visual storytelling that is occurring in the illustrations.

Text

The textual narrative is an obvious environmental allegory. It is a cautionary tale for young generations to maintain a level of awareness and interest in protecting and sustaining the world’s natural resources. Executed in the recognizable Dr. Seuss voice and style, young readers are immersed in an environment that is a fantastical augmentation of their own world.

Suess writes of the harrowing truths of industrialization. On one hand, we are introduced to the loveable Swomee-Swans, Brown Bar-ba-loots, Truffula Trees, and Humming-Fish who have obvious real world parallels. The ugly and destructive elements of industrialization have a similar presence, markered as the Super-Axe-Hacker, and Gluppity-Glupp/Schloppity-Schlopp.

At the center of it all is a Thneed, “A Thneed’s a Fine-Something-That-All-People-Need” (Seuss, The Lorax). The Lorax goes on to challenge the Once-ler of the Thneed’s uselessness, but that doesn’t stop the demand for it. The horrors of supply and demand immerge as the stories moves on. We are delivered thinly veiled descriptions of starvation (“crummies in tummies”) and gills clogged with industrial waste (“No more can they hum, for their gills are all gummed” (Seuss, The Lorax). While playful in their wording, the realities Seuss talks about are harsh and filled with pain and consequences.

It is hard to read the text without feeling compassion for both the creatures and their rapidly disappearing landscape.

Image

The Lorax presents a visually stunning narrative. Choice of color is ultimate for Seuss in developing this narrative.

The opening pages are commanded by dark, gloomy greys and faded purples. A dark night sky accompanies a generally dead landscape of twiggy trees as far as the eye can see. Even the clouds are grey in the night sky.

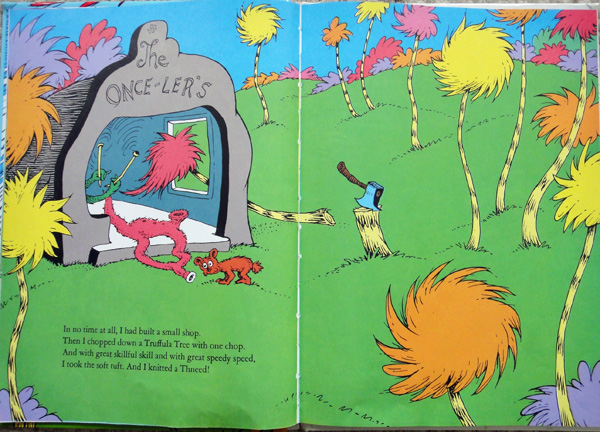

When the Once-ler begins recounting his story, the color palette takes a drastic turn. Bright yellows and pinks, blues and whites, and a dominant green spills over the pages. Each creature is given a bright color that matches the natural setting they reside in. The only grey at this stage is the creature pulling the Once-ler’s wagon.

As the Once-ler sets up shop, he throws out greys and purples back onto the page.

Seuss masters the use of whitespace in the appearance of the Lorax. At this particular point, we are given a stubby orange figure against a white backdrop with a dominance of green on the page. To contrast the inside and outside of the shop, more whitespace is used and the landscape is dwarfed with the repetitive “I speak for the trees!” being delivered to the Once-ler.

Seuss masters the use of whitespace in the appearance of the Lorax. At this particular point, we are given a stubby orange figure against a white backdrop with a dominance of green on the page. To contrast the inside and outside of the shop, more whitespace is used and the landscape is dwarfed with the repetitive “I speak for the trees!” being delivered to the Once-ler.

The obvious visual move that slowly evolves is a move from the greens, blues, yellows, and pinks to the starting colors of grey and purple.

The circular use of the color palette paired with the textual narrative allow readers to understand the way that the story is being told. The images do not simply compliment the text, they are an inseparable part of the narrative.

The visual elements add depth, but also act as emotional cues for young readers.

Whether reading this from the left or the right, for or against industrialization and environmental impacts of corporations, the storytelling techniques that Seuss works with are compelling.

One class isn’t enough to talk about the impact of color in Dr. Seuss. It would be weeks of wonderful conversation.

But as an aside, this was a nice deconstruction of color. We haven’t had much time in class to discuss specific creative choices, such as a color, and how they are edited to be “approved for children.” Christopher’s does draw our attention to this and I can appreciate this lens of thinking.

Can we spend the entire class talking about the emotional cues that colors in picture books give readers?

(I’m only half-joking.)