Primary – Eric L. Tribunella, “Between Boys: Edward Stevenson’s Left to Themselves (1891) and the Birth of Gay Children’s Literature.”

So, the rest of you have done an incredible job with blogging this week.

In an effort to have a little fun with this, let’s put the primary text, Left to Themselves, through some distant reading. To do this, the full-text of the original work by Stevenson is pushed through Voyant-Tools, a suite of natural language processing (NLP) modules, to attempt to garner some new insights into the text. In direct opposition to close reading, distant reading, done with the help of NLP, takes a top-level high-distance approach to literature inquiry.

NOTICE: For readability and the purpose of this blog, this will be kept relatively simple.

LINK TO TOOLS/DATA USED IN THIS POST.

Let’s start with some standard elements. The text contains a total of about 63,000 words. Of that large bag of words, there are only about 7,800 unique words used in the text. Knowing this, the use and frequency of certain terms can be seen as an authorial choice to signify/identify/codify a certain idea or theme of the text.

Figure 1

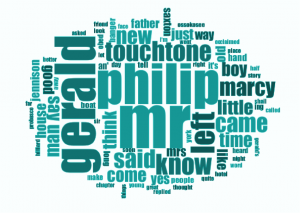

When working with distant reading through natural language processing, one familiar product that we can create is a word cloud. The cloud shows the most frequently occurring words in the text. The larger the word, the more it appears. Stevenson’s protagonists in Left to Themselves, Gerald (379 appearances) and Philip (396 appearances), take center stage here as along with “Mr” (462 appearances). The word “touchtone” also has a large presence in the text which let’s the distant reader understand that the telephone is a major element in the text.

Figure 1 shows a strong presence of masculine identifiers in the text: father (80), man (96), boy (100). The text linguistically maintains a masculine dominance from this sort of filtered view.

So here is where we begin to have fun. Eric Tribunella uses much of his commentary to discuss the use of “human nature” to codify homosexuality into the text. How often does nature appear in the text? It appears twice.

| thinking that he was resisting | nature | successfully, and that his ears | 1) Skip to main content web texts… |

68094 | |

| and anxious to think of | nature | . They met nobody yet. The | 1) Skip to main content web texts… |

70149 |

Okay, so Tribunella does address that the word itself isn’t necessarily used but language based hints are:

“In his preface to Left to Themselves, Stevenson uses similar language to hint at the possibility of boy readers who may want to read books depicting same- sex desire: “But there is always a large element of the young reading public to whom character in fiction, and a definite idea of human nature through fiction, and the impression of downright personality through fiction, are the main interests—perhaps unconsciously—and work a charm and influence good or bad in a very high degree” (n. pag.). That some children read literature for traces of a particular nature hints at the possibility of those who may be looking for characters who experience same-sex desire” (Tribunella).

And right when we begin to question the validity of this exploration, we are struck with this little gem. In searching the term “love” in order to explore the statement that Stevenson switches from friendship language to language of love (379), we are able to find this:

“But — if one yields to the temptation to be among the prophets, and closes his eyes, there come, chiefly > pleasant thoughts of how good are friendship and love and loyal service between man and man in this rugged world of ours ; and how probable it is that such things here have not their ending, since they have not their perfecting here, perfect as friendship and the service sometimes seem” (Stevenson).

At this point, it is obvious that applying NLP to texts such as these in comparison to secondary works like the one produced by Tribunella, we can gleam new perspectives in our research.

I implore all of you to take a moment to poke around in the above data link and see what you can find out about Left to Themselves from a distant perspective.