I eagerly signed up for this week as my primary blog post because I wanted to write about The Giver. As soon as I started reading Second Generation Memory, though, I realized my primary blog post would be totally different. And somewhat long, so tip: the actual analysis is at the end, but I have quite a bit of setup first.

Anastasia Ulanowicz writes that “the child of concentration camp survivors is profoundly aware of the fact that she might not exist if the material circumstances and series of events that her elders encountered had varied even to the slightest degree” (15). I am not actually the child of survivors, but my parents both are. I’m a grandchild of three survivors. And I was always profoundly aware of the fact. If my grandmother had not been smuggling sugar across the Polish-Russian border to feed her family, if the Russians hadn’t caught her and sent her to Siberia where she met up with her father and brothers who had been captured earlier, she would have been sent to Auschwitz with her mother, sisters, and younger brothers a week later. They were all killed immediately upon arrival. She would have been killed, I would not exist.

I never heard that story from my grandmother, though. I heard it numerous times from my mother, her daughter.

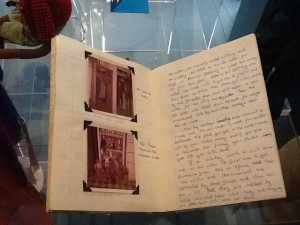

My other grandmother was sent from Vienna to England on the Kindertransport, an initiative sending children out of troubled zones to England at the start of the war. She never spoke about it either. But when she and my grandfather were visiting once, she saw a book on my nightstand – Far From the Place They Called Home. It’s a popular Jewish Young Adult novel about five boys sent on the Kindertransport. She read it in one night, and the next morning she sat next to me on the sofa, held my hand, and told me about how she and her brother escaped, how her mother was brought over later as a cleaning woman, how they went to the countryside in Scotland when London was being bombed. That was the most I’ve ever heard her talk about the war.

I wanted to ask her which town in Scotland she stayed in, but she passed away seven years ago, before I ever asked her.

Growing up, we heard story upon story of life “before the war,” and about the strength and faith of individuals and groups during the war and just after liberation. The stories of atrocities we got from books.

For my primary response, I’m going to provide a perspective that Ulanowicz doesn’t cover, one that isn’t covered in most surveys or discussions of children’s literature: the literature of the Orthodox Jewish community. It’s a literature exclusive to Orthodox Judaism, published by Orthodox publishers and sold in Judaica stores. These are not very accessible outside of the cloistered Orthodox communities. Though some Orthodox Jewish children do, to varying degrees, read non-Jewish books, we never did read secular books about the Holocaust. My purpose here is to explore how second generation memory as Ulanowicz describes it works in this specific demographic and with this specific set of literature.

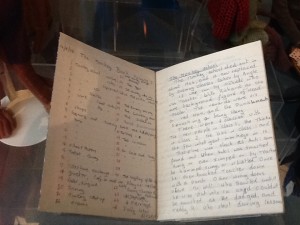

Ulanowicz clarifies that she focuses on the texts’ representation of and contribution to the conceptualization of second generation memory, but that she refrains from studying human response to the texts, leaving that to psychologists and reader response critics (20). I’m going to be that reader response critic here, drawing on my own experiences, on those of my friends and sisters, and on what I observe in the shift of Holocaust books from my own generation to the current generation of children’s Holocaust books. Following is a kind of annotated bibliography, with an analysis at the end. I’ve divided them roughly into four categories: 1) “early” memoirs, 2) “early” fiction, 3) later memoirs, 4) later fiction.

1) “early” memoirs:

Sisters in the Storm, by Anna Eilenberg (1992)

Part of the series The Holocaust Diaries. The first Holocaust book I read, as a ten year old. My sister says she read this when she was seven. (This is the typical age. Important details for thinking about how and when second generation memory is formed.) Chana (Anna) lives in Lodz, Poland and is forced to move with her family into the Lodz ghetto. Conditions are terrible, and she is eventually sent to two different concentration camps. The abridged version I read as a child ends with liberation and displaced persons camp, but the full version follows her to Israel and details the rebuilding of her family, her marriage, children, and grandchildren.

Some of the episodes that I remember vividly to this day:

– She and her sister sneaking out to join learning groups for girls, risking their lives because the Nazis were patrolling the streets.

– Her brother being told by the doctor that he’s very sick and needs to eat meat, but refusing to do so because the only meat available was non-kosher horse meat. He dies a week later, revered and respected for his conviction.

– Her father stealing wooden fences to heat their apartment and their Polish neighbor informing the Nazis and then revealing his hiding place when the Nazis were looking for him.

– The Jewish kapo beating the inmates until they were bloody because she had been praised so much by the Nazi guards that she stopped identifying with her Jewish sisters.

Those Who Never Yielded, by Moshe Prager (1997)

Originally written in Hebrew and translated to English. Short stories detailing teenaged boys in ghettoes and concentration camps who defied the Nazis. Defiance is exhibited by observing holidays and organizing prayer groups even at the risk of death.

2) “early” fiction

A Light for Greytowers, by Eva Vogiel and Ruth Steinberg (1992)

Miriam and her mother escape Russia during the Czar’s rule and flee to England. Miriam’s father has fled earlier, but they have no way of contacting each other, and husband and wife are desperately trying to find each other. Miriam winds up in an orphanage, which is run by a draconian woman. Miriam finds out that all the girls there are actually Jewish, and she leads them in a revolution against the witch-like Miss Grimshaw. They begin to observe Shabbos and keep kosher. Miriam’s mother and father find her and each other at the orphanage, Miss Grimshaw flees in disgrace, and all the girls get a loving warm Jewish house mother – Miriam’s mother.

A Thorn Among the Roses, by Eva Vogiel (1990s)

First of a series. After the war, young girls are left homeless and distraught. A few women set up a school in England’s countryside where they can begin life anew. Intrigue ensues in the form of an anti-Semitic neighbor and his accomplice (who is inside the school as an employee disguised as a Jew), danger and kidnapping of two girls, and eventual reuniting and safety at the school.

3) later memoirs

A Boy Named 68818, by Israel Starck, as told to Miriam (Starck) Miller (2015)

I haven’t read this one, but my sister gave it to me when I went to pick up the others… The title is a reference to the numbers tattooed on the arms of concentration camp inmates. In lieu of a summary, here are some blurbs from the back of the book:

“A spellbinding book. Starck is an ember saved from the inferno of World War II.”

“Starck’s unpretentious account and his extraordinary courage tested in the hellfire of World War II reveals his faith and humanity and will surely inspire young people to treasure the richness of faith.”

“Srulek’s [common Hasidic nickname for Israel] strength of spirit enabled him to survive and thrive. This is a story that should be shared!”

4) later fiction

I don’t have any particular titles for this category, but here’s a sweeping generalization: Novels of the past decade tend to be either thrillers or emotional tearjerkers, and almost all of them are set against a backdrop of Holocaust memories or Holocaust survivors. Sometimes the heroes need to go to Europe, where they come up against a number of obstacles related to remnants of anti-Semitism. Sometimes the entire story is framed around a young person’s response to their grandparents’ stories. Almost always, in Ashkenazic Orthodox teen literature, the Holocaust exists as a natural component of life even when the entire story has nothing to do with the Holocaust. Rarely does a book go without a single mention of the Holocaust.

5) One more category: songs and movies.

In eighth grade, we watched a film called To Live Forever. Since then, I have tried numerous times to find it, with no success. It’s basically a really mournful musical soundtrack with black and white photos of the Holocaust, including some of the most famous: the boy in the Warsaw ghetto with his arms raised, the man standing silently with his chin up as Nazis laughingly cut off his beard, children with hollow eyes and bones showing through their skin, lying on the ground. These images are in the second video below, though I don’t think they ever showed us the really graphic images of bodies.

Many many English-language songs are about aspects of the Holocaust:

(Both of these songs are frequently sung in summer youth camps and at various high school events.)

Analysis

I termed the books from the 1990s early because that was when, I think, survivors first began to write down their memories. Of course, as Ulanowicz makes clear with her examples of Judy Blume and Lois Lowry, books about the Holocaust were being published before that. But not in the Orthodox world.

The early memoirs, though, focused equally on the atrocities committed by the Nazis and their collaborators and on the faith of the heroes and heroines said the cause of their survival. The stark danger of trusting Gentiles was clear – Anna Eilenberg details how her Polish neighbor, with whom they’d been very close before the war, betrayed her father to the Nazis when he was hiding from them in the attic.

The early fiction focused on rebuilding, but again emphasized the dangers of interacting with Gentiles. Fiction was more likely to focus on teenagers with teenage voices, while the real accounts may have chronicled a teenager’s experience but was always told in the voice of an adult – these were memoirs, meant to sound raw. Until I checked the publication dates now, I had always assumed these were written way earlier than the 1990s, because they focused so much on the years just after the war. Now that I know when they were written, I would guess that even after so much time, rebuilding was so important that it made sense that played such a prominent role. If the 90s hadn’t seen that boom, I’d assume that today’s Orthodox Holocaust fiction would be emphasizing rebuilding. Since the books of the 90s did it, it’s no longer necessary, as I’ll explain further below.

The later memoirs are most often written by children of survivors taking down their parents’ words. They are more about anguish and crying out to God. The danger of associating with Gentiles is less emphasized. My hypothesis is that the children (now adults) writing these stories down have so absorbed the lessons they learned from the earlier accounts that this danger is no longer an essential component to emphasize. Instead, they focus on the memories that tie Jews of faith together – the anguish that elicits cries for help directed at God.

Later fiction may have a storyline based on events of the Holocaust, but more likely is the Holocaust as a “ghost” in the background – exactly as Ulanowicz describes second generation memory, but this is the third, or more accurately fourth, generation after survivors.

The second generation absorbed the horrors of the Holocaust not as ghosts but as Inferii: real, tangible, bursting out of the water in frightening solidity. Ulanowicz’s dismissal of the term “dominate” as a description of the past’s effect on the present of children becomes relevant again in this context. Later generations, the generations who received the memories from the second generation, experience the memories as ghosts – filmy, transparent, fading against the wall and barely noticeable, but still there – finally superimposed on and merging with the present as Ulanowicz describes, but not taking it over completely.

Specifically Orthodox representations of memory always include a reference to faith. It was faith that kept the people going and allowed them to survive, according to these books. It was faith that allowed them to pick themselves up and rebuild their lives afterwards. And their faith was strengthened from having experienced these horrors and the resultant “obvious” miracles and grace of God. (This insistence is the reason secular books, especially about the Holocaust, are banned.) Children and teens reading about and identifying with the characters who experienced the horrors but persevered in their faith would picture themselves in the same situation.

But while the books Ulanowicz discusses accomplish identification with the result of children learning to be more tolerant of others, to spurn racism and anti-Semitism, Orthodox books do this with the result of ever more closed boundaries and ever more fear of outsiders. The methods and the general concept are the same; the outcome is quite different.

To close, I’ll transcribe the lyrics to two songs from my high school musicals, to illustrate the extent to which even fun high school entertainment becomes imbued with all of these memories and values. Both of these plot lines are based on the Holocaust, Peace by Piece (1997) happening to the children and grandchildren of a survivor, and Not Enough Tears (1998) during the war, in the US with the protagonist having escaped from occupied France.

Peace by Piece (1997):

My father by the Nazis was taken away,

In a concentration camp he arrived one day.

In a factory of tea kettles he would work nonstop,

Melting the handles well, attaching them to the teapots.

[…]

Father’s fingers swiftly worked under the table.

He would finish his quota early so that he would be able

To put on tefillin [black prayer boxes] just for a moment, to daven mincha [pray] too

A day without a tefila [prayer] wasn’t living for a Jew.

Not Enough Tears (1998):

So many teardrops falling, collecting through the years,

When tragedies unfolding, leaving a trail of tears.

My life was torn and shattered remembering the years,

When nothing else had mattered, leaving a trail of tears.

Hard as they have tried to rejoice when we have cried,

Yet the day will come we know, our tears will be their sorrow.

Tears of anguish will be replaced, and the tears of joy will roll down our face,

As we once again begin to reunite a tattered nation.