A colleague of mine, Martha Joy Rose, recently completed an MALS in Motherhood Studies at the GC.

Here are some resources:

http://mommuseum.org/mother-studies/

https://gc-cuny.academia.edu/JoyRose

A colleague of mine, Martha Joy Rose, recently completed an MALS in Motherhood Studies at the GC.

Here are some resources:

http://mommuseum.org/mother-studies/

https://gc-cuny.academia.edu/JoyRose

I’d never heard of childhood emancipatory studies before reading this article and I’m still not totally sure I understand what it is—I found this to be one of the least accessible pieces we’ve read this semester. But my sense of the field—at least how Mary Galbraith sees it—is that it is an interdisciplinary one (with a strong bent toward psychoanalysis) that roots itself in the subjective experiences of children, who are often marginalized and silenced. Galbraith proposes that we need to emancipate children by “understanding the situation of babies and children from a first-person point of view, exploring the contingent forces that block children’s full emergence as expressive subjects, and discovering how these forces can be overcome” (188). But for Galbraith, the way to accomplish this is adult-centered: “through adults transforming themselves and their own practices” and “reevaluat[ing] their own childhood experience as part of a personal emancipatory human project” (188-89).

While I think this is a valid idea, I think that Galbraith fails to emphasize the intersectionality of difference sorts of “emancipatory studies.” There is an enormous discrepancy in how silenced or marginalized a child is depending on his/her socioeconomic status, race, gender, learning or cognitive dis/abilities, family background, etc. For example, studies have shown that students of color are penalized more often and more harshly than their white peers at schools across America. (See below for some articles about these studies.) This type of research comes out of sociology or anthropology, fields I didn’t really see Galbraith giving much of a nod to compared to psychoanalysis and philosophy. In a field like childhood emancipatory studies—or really, any field that’s attempting some sort of understanding of someone’s “subjectivity” who isn’t ourselves—it’s especially important to be mindful of cultural difference. Maybe combining multiple emancipatory models—Galbraith lists liberation theology, feminism, and pedagogy of the oppressed as examples outside childhood emancipatory studies—would allow for more nuanced and comprehensive analyses of emancipation.

Ultimately, what I found most compelling about this article was how Galbraith questions “postmodern skepticism”—which I too have found frustrating. For Galbraith, a key problem of postmodern analysis is “showing theoretical access or even existence” of childhood or other experiences outside ourselves, which can hinder any sort of scholarly conversation about childhood whatsoever (191). But I wonder if a postmodern, skeptical reading is really all that different from the approach that Galbraith encourages and attempts. For example, Galbraith’s analysis of the Polar Express seems based in a certain kind of skepticism of traditional readings of children’s stories. And although, like Kate, I find her analysis of Polar Express with Santa as Hitler-figure questionable at best, I do see how using an approach like Galbraith’s—one that encourages that we question our presumptions and traditional modes of understanding—can be very useful in studying children’s literature and in fact go hand in hand with the type of postmodern criticism that Galbraith seems to oppose.

Articles about race and disciplining in schools:

http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/new-data-us-department-education-highlights-educational-inequities-around-teacher-experience-discipline-and-high-school-rigor

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/us/higher-expulsion-rates-for-black-students-are-found.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/03/21/292456211/black-preschoolers-far-more-likely-to-be-suspended

Notwithstanding my disagreement with Galbraith’s reading of The Polar Express, I was fascinated by the rest of her article. Here are a few responses.

I admire and agree with Galbraith’s interest not in “an apocryphal ‘child reader’ but on different ‘children’ in the literary transaction who can be approached as individual beings who have left a verbal and artistic trail that can be studied: individual child characters, the unique childhood of the author, and the unique childhood of the critic” (200). I feel rather strongly that children are just as diverse in temperament and interests as adults. Is the child innocent or not-so-innocent, whatever that means? It depends on the child.

Gratefully accepting Galbraith’s license to reflect on my own childhood, I vividly recall my disdain for the philistine tastes and preferences of other children my age; I also remember frequently thinking that many of my classmates were jerks, prone to bizarre, obnoxious behavior that my mother explained as “negative attention-getting.” Nothing made me more indignant than an adult’s assumption that I shared the primitive tastes of others my age, or that I failed to notice and feel appalled at other children’s antisocial behavior. I guess I was an uptight kid. I cringed at adults’ presumptuous statements of “kids like this” and “kids think that,” statements that seemed to explicitly deny me individuality and subjectivity (though I didn’t know the word for it then). I felt that adults that insisted on such essentializing dogmas did so because they were philistines themselves as children and had somehow managed to reach adulthood without noticing anything beyond their hopelessly limited perspectives. Or perhaps they did know better, but nevertheless insisted that “kids are all the same” for the sake of convenience and the blissful intellectual laziness of categorical, black-and-white thinking.

My indignance must have abated when I was finally old enough to escape feeling personally implicated by such statements because I haven’t thought about these outrages for a long time. Until recently, in fact, I had tended to lump young people together in that noisy, messy, tedious category of kiddies—squalling, Raffi-listening, Barney-loving monsters—without allowing for outliers and for the diversity of temperament of which I was so keenly aware as a young person myself. It’s so easy to view children this way.

But while my own assumptions might have been intellectually lazy indeed, I may have judged the essentializing parents and teachers too harshly in light of the deeply-ingrained social orders that render authentically individualized treatment of children much easier said than done. Hopefully, sometime in the future we will enjoy a sufficiently safe society that children will not have to be incessantly guarded, supervised, and surveilled, and therefore constantly lumped together to facilitate such policing, but as it is, child-rearing resources are limited and efficiency is premium. Children who all like the same things and think the same way are much more efficiently managed, like an obedient hive, than a collective of distinct, individual young people. I say this not to defend conventional western child-rearing practices, but to direct the blame for them towards the socioeconomic structures that impede more individualized, emancipatory practices.

In other words, I agree with Galbraith, and I believe (yes, the bell rings for me!) in the potential of “adults transforming themselves and their own practices” (Galbraith’s emphasis) instead of trying “to mold children through training them” (188). But even though we and Galbraith are talking about methodological approaches to children’s literature rather than clinical, “real-world” applications of psychological methods, I feel compelled to point out the extraordinary impediments to attachment parenting in western culture. I’ve only recently noticed this phenomenon, and I’m so dismayed by it, I hope you’ll indulge me for a moment. Parents cannot take their young children to work (they really, really can’t, no matter what their jobs are), and—in the vast majority of cases—work they must, every day and all day. On-site child-care is a nonexistent unless you are one of the lucky few employed at an uber-progressive start-up or university, and even then, chances are very slim that the option will be available. The result is a widespread, daily routine of unpreventable, extended attachment breaks for the vast majority of young children. After reading Galbraith’s article and a bit of Alice Miller’s work, I find this state of affairs really alarming.

Social structures also frustrate parental attempts of “transforming themselves and their own practices” in even more subtle, insidious ways. I had terrible insomnia throughout my preschool to school-aged years, and I vividly recall the nightly despair of lying awake in the dark for hours, trying to remember movies I’d watched scene by scene and playing bizarre games in my head because, like all children, I wasn’t allowed to just turn the light on and read like normal adults do. Bedtime and child resistance to it is so ingrained and normalized that the bitter, one-note comedy of Go the Fuck to Sleep has made it a beloved bestseller. Go the Fuck to Sleep reinforces the hegemony of bedtime instead of questioning it, but it also offers sympathy for the problem of alternatives to enforced sleep habits, particularly when those parents must also “transform themselves and their own practices” to satisfy the demands of contemporary capitalist western society. In a better world, parents could decide to open their rag-and-bottle shops late if they’ve been up all night with the baby, but in this world, parents must clock into their jobs at an exact time without exception and must perform those jobs with such robotic consistency that the rest of their lives, including their children’s sleeping habits, must be arranged to enable parents’ capacities to satisfy the expectations of corporate employers (who are, in turn, legally obligated to arrange their companies to maximize shareholder profits, not employee well-being). In other words, the parents have to sleep so they can function well as employees, and therefore insomniac children must lie awake in the dark wondering why their individual, biological needs are so painfully ill-matched to their inescapable circumstances.

I have great parents, but childhood is hell even under the best of circumstances. Bad things—things we would find utterly intolerable and unfairly punitive as adults—are constantly happening to children to the point that this “badness” (to take a word from a certain special French child) can be understood as a fixed expectation in a child’s daily life. Frustration, disappointment, and a veritable carnival of irritations and harassments are constant in the lives of children. Children’s desires are routinely denied for many good reasons, but children also must constantly cope with conflicts between their natural urges and whatever they are being forced to do. I will venture to say that adults have a lot of little habits that contribute to their well-being which are forbidden to children. If we really need the cookie, and are going to lose our minds if we don’t eat the cookie, as adults, we can just eat the cookie and get on with our lives; kids can’t, and therefore lose their minds. If we are in some uncomfortable situation where we truly cannot stand the way people around us smell and look at us, we can usually make our excuses and flee, but children are trapped. If we’re hot, we, as adults, can take our jackets off, but babies cannot, and have no way to articulate their discomfort, and no guarantee that their needs would be met even if they could express them. My own memories of such childhood frustrations awaken my empathy in ways that otherwise stay dormant when I feel tormented by a screaming baby on the subway, for instance.

I grant that my current memory of these childhood experiences are probably contaminated by innumerable presentist distortions, but they might also be perfectly accurate, and I’m grateful to Galbraith for acknowledging the revelatory potential of considering one’s own first-person, subjective experience of childhood. If I automatically dismissed these kinds of personal reflections as distorted to the point of zero value, I would shut down consideration of a view of childhood with emancipatory potential. We can easily critique humanist disregard for categorical differences as its own form of oppression in its denial of real alterity, but attempts to identify with the Other’s first-person, subjective experience—empathy across categorical boundaries—can expedite movements in the direction of emancipation. Insisting that emancipation is only possible when the oppressed can speak for themselves dooms babies and young children, animals, and those without language to their present conditions. Insisting on the unknowable alterity of the very young and the universal fallibility of childhood memories entrenches the status quo and shuts down inquisitive, open dialogue between children and adults. I love Galbraith’s characterization of indirect approaches to formulating childhood experience, including episodic memory and revisiting one’s own subject position in childhood, as “fingers pointing to the moon,” but not “the moon itself.” That seems like a really good start.

I think I’ll stop here, but to summarize: I’m quite persuaded by Galbraith’s support of Miller and deMause (among others) and their psychohistorical analysis of the causative link between normalized early childhood parenting practices and adult atrocities. I also agree with the contention that children’s literature presents “SELVES [why does she capitalize this?] in predicaments from epistemological perspectives unavailable to ordinary interaction, but resonant with our own vulnerability as embodied creatures” and therefore that children’s literary criticism is a valuable indirect means of accessing childhood experience, particularly if the individualities of all involved (readers, authors, critics, characters) are taken into account (193). Legitimizing the attempt to access one’s own childhood experience seems to offer more emancipatory potential than the “’brashly accepted helplessness’” of foreclosing the possible accessibility of childhood memories. At the very least, validating such reflection offers more chance for empathy for the children’s suffering in the yoke of normalized child-rearing practices, and little risk of making things worse considering the inherently dependent relationship of children on adults. But actually preventing Hitlers and Bartsches from continuing to sprout up requires attention to the structural impediments to emancipatory practices, and these arise from western capitalist society’s deeply rooted ideas about professionalism and its belief in the need to sequester young children and parenting modes altogether from the world of professional work. Fortunately, such considerations are also a job for literary scholars, among (many) others.

I’m going to be a little sneaky here and double-post because I have so much to say about Galbraith’s article. This post is about her reading of The Polar Express; later on I’ll post some thoughts about her broader discussion of emancipatory child studies (which blew my mind).

I think Galbraith’s one misstep in this fabulous article is her reading of The Polar Express. I agree that the image of masses of identically-clothed elves gathered to greet Santa does resemble a Nazi rally, but it also resembles a rock concert, a royal wedding, and an Obama campaign rally. Galbraith might object that the fact that the elves are all dressed in one color resonates with uniformed Nazis and distinguishes them from these other kinds of democratic assemblies, but consider the popularity of matching event t-shirts distributed at fundraisers, or the wearing of pink at the Avon breast cancer walk. Or Santacon, for that matter. These communities aren’t perfect and suffer plenty of valid critique, but it seems like a stretch to accuse them—and the elves—of being Nazi-esque for assembling en monochromatic masse.

My second quibble with Galbraith is that Chris Van Allsburg was born in Michigan in 1949, so he certainly wasn’t attending any Nazi jubilees during his childhood or adolescence. But what about his family? Even if we humor Galbraith and hypothesize that Van Allsburg’s parents were German immigrants who raised him on a steady diet of their fond childhood memories of Nazi Youth rallies, what are the odds that these vicarious memories inspired Van Allsburg when he had direct access to the many powerful mass assemblies of 1960s America? Why can’t we point out Santa’s resonance with rock stars and civil rights leaders instead of Hitler? Moreover, would we say that Martin Luther King, Jr. and the performers at Woodstock were fŭher-like because huge crowds gathered to listen to and venerate them?

Galbraith claims that Polar Express resonates with “the imagery of a Nazi Youth rally” in part because “a lonely and yearning child travels by magical night train through a Northern European folktale/operatic landscape.” Doesn’t that also describe Harry Potter aboard the Hogwarts Express, complete with uniforms and the intention to see a Great Man, Dumbledore (and the hope to curry favor with him)? Yet Vauldemort, not Dumbledore, is the charismatic leader with genocidal interests. The Nazis simply cannot have the monopoly on magic train imagery. Magic trains are conducive to a liminal, otherworldly atmosphere; my personal favorite magic train might be the one Chihiro rides in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, which also offers a very clear counterpoint to the argument that trains inherently serve as emblems of industrialization and its decay. There is something emancipatory about the notion of train travel, especially for a child; it has something to do with the fixedness of the stations and schedules, and comforting anonymity of getting on and off without one’s presence affecting the train’s movements or agendas. It also feels, subjectively, very safe and free of traffic and the possibility of collisions; there is none of the free-floating anxiety or unpredictability of air or motor travel. But perhaps above all there is something thrilling about an endless network of train tracks that can go far beyond the horizon of the unknown via a very familiar, safe-feeling, and comforting mode of transit. It would be a shame to write off magic trains as Nazi images.

I also do not accept that travelling through the “Northern European folktale/operatic landscape” must resonate with Nazi imagery. The train climbs “a mountain so high it seemed it would scrape the moon” and crosses a “polar desert of ice.” While that does indeed sound like the sort of fairy tale landscape that the Nazis coopted for their own propaganda, I’m reminded of Percy Shelley’s anxiety about the vulnerability of poetic images to perversion, and his injunction to avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Instead of retiring these images permanently for such contaminating associations, we should reclaim and rehabilitate them, perhaps as images of the Romantic sublime, for example. Whenever a particular aesthetic becomes firmly associated with a movement, the aesthetic and the movement risk damage to the other, and sometimes for no good reason. For example, until recent efforts to rehabilitate the aesthetics of the environmental movement, “going green” was so firmly associated with hippie aesthetics, people could hardly recycle without worrying their neighbors would see them as tie-dye wearing, unwashed stoners. On the flip side, the negative associations of so many kinds of aesthetics have left us with the whitewashed minimalism of modern design for the last sixty or seventy years, as though retaining the more ornamental aesthetics of the past would somehow perpetuate the social problems of earlier eras as well.

Next, there is the matter of Polar Express’s reference to the factories at the North Pole, which could be construed as glorification of industry, another Nazi red flag. But the factories also serve a greater, less political purpose as bridges between the impossible logistics of the highly figurative Santa Claus fantasy and the more literal fantasy of Santa’s functioning in accordance with the laws of physics. Obviously, even if Santa had the vastest army of elves and unlimited access to the most advanced technology, he still couldn’t distribute toys to all the boys and girls (leaving aside, for the moment, the also-obvious fact that the majority of children are not Santa-believers) in accordance with their personal wishes and surveillance intel as to naughtiness or niceness; on this, I believe, we can all agree. The industrialized version of the fantasy is still a fantasy; it’s just a different kind of fantasy—one that can perhaps temporarily stave off an older child’s skepticism about the logistics of a pre-industrial North Pole, but which also begins to introduce some of the problematic social realities that lie beneath the fantasy without ramming them down the child’s throat. The book doesn’t develop this much, but the inordinately creepy film adaptation of Polar Express portrays the North Pole’s toy factories as sinister and dangerous places where one clumsy slip could cost a child his life. Isn’t this a gentle but firm introduction to the reality that most toys are produced in sinister, dangerous third-world factories by oppressed workers? The elves aren’t Nazis so much as quasi-enslaved factory workers. Moreover, the children arriving on the Polar Express aren’t new recruits bound to join the ranks of the elves; the children are mere tourists on a temporary visit to the North Pole. The elves, on the other hand, are Santa’s permanent laborers; nothing suggests their ability to board the train back to civilization or the availability of any means of crossing the “polar desert” in which they are stranded in their labors. In the film adaptation, elves speak to the children in a particularly ominous way that suggests significant resentment against these privileged beneficiaries of their labor. It’s a far cry from a heavy-handed Marxist message, but still, the film and even the book plant the seeds of the ideas that toys are not made by happy elves in cozy pre-industrial workshops.

One last point about Galbraith and Polar Express: Galbraith presumably objects as anti-emancipatory to the narrative of a lonely child “chosen out of a crowd for a special gift from a powerful and charismatic adult,” and I agree with this to an extent. But the gift and its presentation are merely rewards for the story’s precipitating action: the boy’s choice to get on the train. The story is telling us that sometimes opportunities and adventures come along in life and yield their rewards only to those who actively choose to grab them. For the young, such opportunities often appear via those who are older and more financially, socially, or professionally established in the world of adults. The book (and the film) take care to emphasize the boy’s agency; the conductor tells him he doesn’t have to board the train. (Of course, if the train conductor turned out to be a molester luring the boy into his vehicle with promises of Santa Claus, we would have a very different story.) Perhaps that’s the other reason why the mode of transit must be a train, which always remains an open, public space and thus precludes the privacy required by contemporary predators (and yet another reason why the Nazis cannot have train imagery). But the point is that even if the reward is bestowed by a “great man,” the principle choice is still the boy’s. There is also some emancipatory potential in the fact that the opportunity does not arrive through any mainstream or normative channels; again, it’s a magic train, and the conductor is not an authority figure from the child’s life. The boy ventures outside of the familiar, normative, highly regulated environment in which he dwells, which strikes me as a grab at freedom.

Writing in 1997, Richard Flynn draws the state of the art of our field of interest. Even though by the time the study of children literature had already become institutionalized, he denounces its persistent marginality and its reputation as “a form of academic transgression.” (144) Namely, he places emphasis on the struggle that scholars working on children literature had (and nowadays still have) to endure in order to be taken seriously.

According to Flynn, it is particularly important to investigate the concept of childhood as both a contested and elusive site, it being “a wonderfully hollow category, able to be filled up with anyone’s overflowing emotions.” (143) He thus calls for a reconfiguration of the field and a broadening of its scope to enrich both the value of the scholarship it produces and its visibility. His recipe to achieve this goal is “to draw on the finest work in the field of children’s literature by emphasizing its major theoretical concerns and bringing those concerns to bear on other literary, cultural, and social texts” (144). In other words, Flynn encourages an interdisciplinary approach that places the child, rather than a specific discipline, at the center of the discourse. He thus dismisses the dichotomy proposed by British scholar Peter Hunt – to whom he is responding with this piece – between “book people” and “child people”. He underlines how the complexity of childhood as a social and cultural construct can only be efficiently investigated through the employment of a multiplicity of perspectives.

The class readings we have been engaging with over the past few weeks point to the fact that the advices dispensed by Flynn almost twenty years ago had a positive impact on the field. I think for example of groundbreaking texts such Rachel Bernstein’s Racial Innocence (2011) and Joseph Thomas’s Playground Poetry (2007), each drawing and reaching out to disciplines outside of the literary realm, such as visual studies, performance studies, and political history. Even more so has done Kenneth Kidd in Freud in Oz (2011), by distinctively bringing into dialogue psychoanalysis and children literature. It would be interesting to find out if and how scholars working in other disciplines – e.g. cognitive science, psychology, and communication sciences – have reciprocated this interest by reaching out to (and/or including) children’s literature in their scholarship. Furthermore, despite this (relatively) newly found interdisciplinary verve, our class discussions have left me under the impression that committing to children’s literature as one’s primary field of scholarly interest still ignites dreadful fears of inadequacy – more precisely, of not being taken seriously both within the academia and outside it. That is particularly puzzling, considering the importance attributed to the realm of childhood in the great majority of fields of study. Why is that different in the domain of literature? What puts babies (and children) in the corner – pun intended – in English Departments? Is the investigation of children culture really deemed as empty of social and practical consequences?

In his manifesto, Flynn also calls attention to the representation of children in literary works for adults. He does so by bringing up the ambivalent figure of Pearl in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, which synthetizes the ambivalence that has characterized the discourse on childhood from the Romantic period up to the present-day. The tension between the conception of the child as “good seed/bad seed” (143) is one that scholars in childhood studies must embrace, for the friction between such contradictions generates sparks and ambiguities worth investigating. The broadening of the scope of our research to the representation of children in texts that are not primarily aimed at them finds me in complete agreement. Children are equally exposed to those representations, especially when it comes to media they can access freely and independently (such as television, or digital platforms). Most importantly, despite the identity of the audience – be it readership or viewership – those cultural artifacts are also places where the concept of childhood is constructed. In other words, the way children are depicted and treated in cultural artifacts aimed at adults also determines the way in which society conceives and perceives childhood.

Flynn thus blurs the line between the binaries that have characterized the field: between adults and children; between past and contemporary texts (he very cleverly underlines that not only the understanding of historical childhood is problematic, as it needs to be screened through contemporary lens, but also that of the present); and, most importantly, he reconciles the figures of “book people” and “child people”, a compromise necessary to gain the institutional power required to “offer significant and powerful corrective to the dominant educational ideologies that threaten children’s legacy and ability to think” (145). His recommendations for the future of childhood studies remind me of the goals set by Stuart Hall for British Cultural Studies. Like Hall, Flynn believes the theoretical in need of being strongly and necessarily tied to a political and practical mission that would redeem the reputation of our work as empty of consequences.

In Freud in Oz, Kenneth Kidd’s “main goal has been to describe rather than analyze” the “historical encounter(s) of children’s literature and psychoanalysis,” as he states in his concluding paragraph. He explores how psychoanalysis used children’s literature in ways that made it seem vital and applicable, and also how children’s literature incorporated psychoanalytic methods and motifs in ways that made it seem authoritative and therapeutic. Kidd identifies an impressive number of connection points, concentrating broadly on fairy tales, child analysis and Winnie the Pooh, case writing as it relates to The Wizard of Oz, Lewis Carroll and Alice, and Barrie and Peter Pan, Maurice Sendak, YA literature as a genre, and trauma writing for children.

I found Kidd’s chapter on Sendak to be the strongest in the book, perhaps aided by its close focus on the work of one mind–playfully close to a case study, in fact. The chapter is in fact based mostly on just two books, Where the Wild Things Are and Kenny’s Window, a grounding which allows Kidd to boomerang out into the many touchpoints between psychoanalysis and children’s literature (developing his idea of picturebook psychology, child drawings, picture book history, queer theory, Sendak’s history with analysis, Freud’s famous cases, children’s author as therapist, etc.) without the chapter feeling scattershot.

Because there are already two excellent blog posts on this book, I think I’m going to concentrate on two ideas that stuck with me after I was finished reading. Neither is necessarily engaged with some of the fundamental questions of children’s literature and childhood itself that we’ve been exploring this semester, but both are broader questions or thoughts about Kidd’s style of work.

First, while I really liked this work, I found myself wondering what to make of it as a work of scholarship. And I mean this in the most respectful way, as I was pretty swayed by Kidd’s assertion that psychoanalysis and children’s literature were and to some degree are “mutually constitutive.” This is an excellent history — but what avenues does historicizing open for future scholarship? What do we do now that we’ve read Kidd?

Because I was curious how others answered this questions, I actually checked out some reviews of the book, which I’ve added to the course Dropbox in the Kidd folder. They were written by our good pals Karen Coats and Marah Gubar, who in fact both saw this book as opening up entirely different conversations. Coats focuses on Kidd’s neglect of trauma in children’s literature about the black experience in America, and suggests that further scholarship on other American identities is needed. Gubar, on the other hand, is most taken with Kidd’s YA chapter and sees his book as a critical new perspective on how she will teach and interpret responses to young adult literature.

(Side note: I’m super glad that Chelsie was writing on this book this week, because I think her expertise in psychology brings a totally different perspective to my question of what one does with this sort of history!)

My second thing, though this is somewhat tangential to the main concerns of our course, is that I found myself reflecting most often not on the content of Kidd’s book, but on its style, sensibility, and prose. Kidd was an antidote to some of the things I find most alienating about academic writing. Sometimes I feel as though I am reading excellent thinkers whose influences, or the scholars with whom they are in dialogue, are nearly coded within their text. Of course, I acknowledge that some of this feeling has to do with how early I am in my own academic career, but I found the directness with which Kidd interacted with other work to be refreshing. An example I particularly enjoyed comes at the end of the introductory sections of Chapter 3, where Kidd takes a detour to discuss Gubar’s Artful Dodgers:

“While Gubar makes a good case for rethinking Golden Age literature in its cultural and historical context, I am less concerned here with the original literature than with what has been done with and to it. I understand that source texts do not always authorize their aftertexts and that Golden Age authors enjoyed richer, more complex personalities than we might know from ventures in case writing.” [I think this is on page 73…but I have a Kindle version so who knows…]

Yes, asides like these help to demonstrate the breadth of Kidd’s reading, but these signposts for what his work is and isn’t, and what it aims to accomplish, and what work it speaks to were gestures I appreciated. The ruminative nature of this book and its careful qualifications and examinations were intensely appealing to me, and demonstrated a thoughtful curiosity I hope will inspire my own work.

I found Kidd’s clarity even more admirable given the jargon-y nature of psychoanalysis. I expected to be Googling terms all but constantly, but his tone was so inviting and so–is casual the right word?–that I felt neither lost nor lectured to as a reader. Likewise, I found his introduction to be one of the most helpful I’ve read in a while, a welcome contrast to something like the beginning of Rose’s The Case of Peter Pan, whose foreword about child abuse I found disorienting, like a footnote to a case not yet made.

Since Chelsie gave us a great summary of Freud in Oz’s major highlights, I’m going to avoid repeating those points, and instead focus on some of the questions Kidd’s text raises for me. I’m especially interested in how we can read Freud in Oz alongside our last two texts: Bernstein’s Racial Innocence and Gubar’s Artful Dodgers.

One of the most interesting trends McKidd documents is the movement from psychoanalysis – the classical tradition, with its commitment to Freud – towards a more American style psychology, which McKidd defines as a combination of psychoanalysis with “pragmatism and homegrown psychology [that] prefer[s] the perfectible ego to the intractable unconscious” (xxi). McKidd shows how various forms of children’s literature (or, in the case of fairy tales, narratives that were appropriated *into* children’s literature) fit into a pattern of the perfectibility of the ego, often through trauma. The fairy tale is a particularly telling case, since it was initially seen as appropriate for children because it reflected the child’s unconscious (which was merged with the “primitive man’s” ego) – a more psychoanalytical, Freudian frame – and it was later seen as good for children because fairytales were “proto-therapeutic” (12). In this latter view, fairy tales help children negotiate the experience of trauma and eventually meet psychological challenges( (11): they do not just reflect the child’s unconscious, but they help the child progress to a healthy adult selfhood (32). While the fairy tale was refashioned as children’s literature because it was proto-therapeutic, other forms of children’s writing was, for McKidd, therapeutic from the start. Picture books like Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are put a distinctly American twist on psychoanalysis: the child has a safe place to play out his anger (represented by the Wild Things) and returns home, having learned a lesson. As McKidd points out “lovers of Where the Wild Things Are probably do see it not as a child’s version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness but, rather, as a self-help book for children and their parents. It is, in other words, part of the culture of self-help” (130). Young Adult novels, meanwhile, often perform psychological work in which the protagonists experience, witness, or recall some form of trauma, and this trauma is eventually rendered therapeutic (168, 172). Sometimes the trauma is nothing more than the stereotypical “adolescent crisis”; nevertheless, the narrative usually portrays the protagonist “working through” the problem and emerging with a stronger selfhood at the end.

While I find McKidd’s reading of many of these picturebooks and YA novels persuasive, I wonder how we can apply Marah Gubar’s idea of the “artful dodger” to these psychological novels. In other words, if these texts have a psychological aim – the improvement of selfhood through a form of trauma and proto-therapy – do children (and adolescents) always go along with it? Do we see, as in Robin Bernstein’s reading of Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s doll test, a possible resistance to these psychological aims? Therapy (usually) involves a relationship between two people, the therapist and the patient – and as anyone who has read Freud knows, the patient often resists the therapists’ treatment. Here, I’m thinking specifically of the case of Dora, Freud’s fourteen year-old patient who eventually refused psychological treatment when Freud kept insisting that Dora’s trauma came from the fact that she enjoyed the sexual advances of her father’s friend (I find this case particularly striking to think about in relation to Freud in Oz, since Dora is an adolescent). Dora’s case led Freud to consider issues of transference and countertransference (pardon my massive oversimplification of the history of psychoanalysis), and I wonder to what extent YA authors who practice a kind of therapeutic writing are also aware of possible resistance from their patient-readers, and weave that awareness into their texts. Gubar argues that 19th century children’s authors are ambivalent about their subjects, and about their own ability to influence their subjects, and that they incorporate possibilities for resistance into their own narratives; I wonder to what extent that might also be true for the psychological YA and children’s text.

Another trend Kidd identifies is the extent to which the construction of adolescence, especially in the 20th century, is racialized. G.K. Stanley Hall, who theorized the psychology of adolescence and influenced its subsequent 20th century construction, “drew upon racial and racist developmental logic,” particularly the notion of recapitulation, whereupon white children and POC were at the same developmental level (142). White children needed to move beyond the “primitive” development of POC and towards the “civilized” selfhood of whiteness through their adolescence and eventual adulthood; the white child thus “repeats or re-enacts the developmental history of the species” (143). That this theory explicitly excludes adolescents of color from “growth” towards “civilized” adulthood is an unspoken, if obvious, consequence of this construction of adolescence. Moreover, early psychoanalysis draws upon similar racial logic: psychoanalysts saw the fairy tale as revealing the unconscious of both the child and the “primitive” man; the two were made equivalent. Psychoanalysis is racialized in other ways not mentioned by Kidd: for example, Freud and his contemporaries practiced primarily on white patients (and their analysis and theories arose primarily from that work with white patients).

Given Kidd’s contention that YA practices a kind of adolescent psychology, and Kidd’s observation that both psychoanalysis and the construction of adolescence are fundamentally racialized, what does this mean for young adult readers of color, and for children and young adult novels that are aimed towards audiences of color? It seems to me that YA writers of color might have a very different relationship to the idea of YA novels as therapy-through-trauma, or to the idea of adolescence as a growth period, than white writers. Do they write in the same mode as the YA psychological novel? Do young readers of color tend to receive canonical texts in the same way white readers do? After reading Bernstein, these questions loom particularly large in my mind. It’s striking to me that most of Bernstein’s examples of children’s literature with a psychoanalytic bent are by white writers, and have white protagonists (Where the Wild Things Are, Winnie the Pooh, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Judy Bloom, Speak).

I think these questions are why I fixated so much on Kidd’s (very brief) mention of Octavia Butler’s 1979 novel, Kindred. Kindred is one of the only examples Kidd supplies of a novel that deals with race. Kidd brings it up in the context of YA books that have their protagonists “experience first hand the horrors of history” (191). Kidd is primarily interested in holocaust narratives, but he also mentions time-travel and trading-places narratives like Kindred that deal with American slavery.

For me, Kindred was a strange text for Kidd to bring up as an illustration of the phenomenon of protagonists witnessing the horrors of history, in part because it seems like an exception to the rule Kidd identifies – the trend where time travel narratives allow the protagonist to *experience* the horrors of historical trauma, but as a relatively safe witness who can eventually escape. In Kindred, the protagonist Dana is no mere witness. She finds herself on the plantation inhabited by her ancestors – including her enslaved many-times great-grandmother, and her great-grandmother’s owner, Dana’s many-times-great-grandfather Rufus. In order to survive – to literally continue existing – Dana must not just “witness” the horrors of slavery but actively enable and participate in them. She must make sure that her slave-owning ancestor rapes her enslaved ancestor (or she will not come into existence). It would be as though one of the protagonists of a holocaust time-travel novel had to actively participate in the holocaust (rather than just witness it) in order to survive. Part of Kindred‘s project, I would argue, is to show the extent to which contemporary americans are indebted to, and continue to re-perpetuate, race-based slavery and violence. And Dana emerges from the novel more traumatized than when she began.

Kindred, a novel written by a black woman, also serves as an example of my earlier point – that YA novels that deal with race, that are written by or for people of color, may have a very different relationship to the therapy-through-trauma mode of writing than the conventional YA novel. Although here, my argument is rather shaky, since Kindred was not written as a YA novel (and I find it rather bizarre that Kidd includes it, even as an aside). Kidd is correct that high schoolers often read Kindred (it has been incorporated into many curriculums), but I’ve never seen anyone else argue that Butler wrote it with young readers in mind (and Butler did write young adult novels later in her career). In fact, most of the main characters are adults in their mid-to-late twenties, not adolescents or children. Despite the generic strangeness of Kindred, I do think it brings up interesting questions about the ways in which authors and readers may resist the therapy-through-trauma mode of writing and reading.

Hey, y’all! My one stop in London on the way to Edinburgh last week was the V&A’s Museum of Childhood. Funny story – it’s across town from the main location. Which they don’t say on their website. But I had enough time to make it there, and the MoC is not so large that I didn’t have enough time for everything. It’s designed for children mostly, though it’s of course fascinating for a childhood studies scholar.

At some point, I found myself thinking more about how the curators were presenting things than what they actually were presenting. I had intended to upload these pictures along with some of my thoughts on the train up from London because there’s lots of things here that should be interesting for our class or for some of our work. But my technology was annoying, plus the train says free wifi and then charges 9 pounds an hour. So nope.

Which means, here’s a whole slew of pictures, some out of order because I think the order got switched when I uploaded from the camera. Also some are pretty bad quality because the lighting varied. If I can figure out how, there’s one picture (about Pulcinella/Punch shows) that’s really interesting that’s stuck on my camera – I will try to add it later.

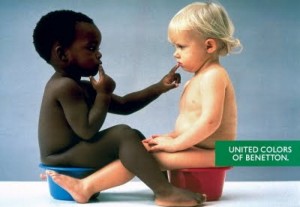

In connection with this week’s readings, here’s a couple of pictures that were part of a controversial advertisement campaign conducted in the 1990s by the Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani for the fashion brand Benetton. Toscani has come to be well known for the shocking pictures employed to shock the viewer on social issues, and themes such as racism, homophobia, imperialism, and so forth. Some of them had become popular (and controversial) not only in Europe, but also in the US.

I was reminded of these two specific photographs because they both subvert the idea of “the loving touch of the white child” that, according to Bernstein’s reading of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “restores Topsy to humanity, natural Christianity, and childhood.” (45)

In addition, I see the second picture as an explicit mockery to racial prejudice, suggesting it does not belong to the innocent realm of children. This representation clearly relies on a Romantic view of childhood, as also suggested by the apparently harmless nudity and asexuality of the subjects (the gender of the children does not appear clear to me in neither of these pictures) . The embrace clearly implies complicity and mutual protection, whereas the grin on the white child is an element of the depiction that attracts me and yet leaves me puzzled. I came up with two different readings for this and I would love to hear your opinion on them, or your personal interpretations if you come with a different ones. At first I thought of it as a mockery of the kids’ appearance, as an evil grin suggesting the naughty nature of the little angel, in clear opposition to the harmlessness of the little devil-looking child. At a second glance, though, it seemed to me more like a defiant grin, a mockery to the racial prejudices of the adult world (the intended audience of the picture indeed).

By the way, you can find more of Toscani’s campaigns here http://www.repubblica.it/cultura/2014/08/08/foto/oliviero_toscani_le_campagne_pubblicitarie_pi_provocatorie-93430769/1/#1 (the website is in Italian, but the pictures are quite eloquent) and an an interview with him here http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/08/13/oliviero.toscani/index.html .

Bernstein’s central argument is that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, white childhood was mobilized as a force of innocence that could make divergent political positions appear natural, while black childhood was made to appear durable and incapable of sustaining harm. This naturalization occurs by way of a quality she calls “racial innocence” (4). Bernstein thus cites instances in many visual and performed texts (such as the illustration of the arbor scene in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the frame story of Uncle Remus) in which a white child’s “innocence” is transferred symbolically to the people or institutions around him/her, furnishing arguments both for slavery and abolition.

Bernstein’s methodology is characterized by a focus on “scriptive things,” (dolls, in particular) which while they “allow(ed) for agency,” also “broadly structur[ed] play” (12). This methodology is particularly apt for her project because her aim is not only to expose the ways in which the kind of innocence typically ascribed to white children constructs and is constructed by racist performances of play and theatre, but to show how African-Americans resisted these scripts. As Bernstein notes, the dearth of information about African-American oral culture and everyday practices during the time of slavery makes it necessary for her to “coax the archive [objects of material culture] into divulging the repertoire [the way in which such objects might have been used]” (13).

This methodology also helps Bernstein get around a methodological problem that is far more general to the field of children’s literature–how to talk about actual children. I think this is easier for Bernstein to do than Gubar because she focuses on the largely self-evident characteristics of “scriptive things,” which by nature can be interacted with in a number of ways, rather than trying to prove that child collaboration with adults existed on a significant scale (as Gubar does). Bernstein uses the sources she draws on (an extensive range of primary sources such as memoirs, periodicals, advertisements, photographs) to provide examples of how individual children used the scriptive objects they were given–not in order to make generalizations about these forms of resistance, but in order to illuminate the contours of the system against which they were reacting. For instance, Bernstein uses Daisy Turner’s reaction to her teacher’s assignment as an example of the long-standing nature of African-American girls’ negative feelings about black dolls. Bernstein does not try to make generalizations about other girls’ resistances from Turner’s obviously exceptional instance; rather, she is interested in the obviousness Turner’s statement implies. As a child, Turner knew that her teacher’s assignment was degrading. By examining this instance, we understand one of Bernstein’s main points–that children were knowledgeable about the scripts of childhood–even if we cannot know hard facts about how many resisted those scripts and how many performed them exactly as written.

The physical characteristics of toys as opposed to verbal texts also helps Bernstein to make her argument. The determinateness of objects like toys, and the directness of the advertising material that often accompanies them, makes explicit how they are “supposed to” be used. This is likely because producers of toys are less concerned to hide their dependence on their child audience; indeed, making it as clear how a child audience would use such an object, makes it clearer in turn, why he or she would enjoy it, thereby increasing sales. Bernstein therefore, does not have to guess about the intentions of these objects “authors,” because they are shamelessly obvious.

Bernstein’s use of primary sources was thrilling for me, because I am becoming interested in authors’ ideas of their audiences–how they conceived of them and interacted with them. In children’s literature, the question of audience has of course been a pervasive one, so this is a fairly obvious question for most of us. In nineteenth-century literature in general, though, I think there has not been enough attention to popular novelists’ ideas of audience, and how these changed as they grew famous and had to rely less on periodical publication to make ends meet. My working hypothesis is that producing work in order to feed a public frenzy for their image and name, rather than fitting their work to the parameters of each individual periodical might have made some authors feel generically confined, which is counter to the popular idea that periodicals themselves made novelists feel confined. I think this is largely because scholars often forget that nineteenth-century novels were as wound up in the material and economic networks of their day as periodicals were. Bernstein shows this with a force that is astounding. Her discussion of how such presumably literary characters as L. Frank Baum’s Scarecrow, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Topsy, were intricately intwined with icons of popular culture like Gruelle’s Raggedy Ann, and the blackface actor, Fred Stone, absolutely blew my mind.

It shows that all these works did not exist as autonomous products of individual authors, but that they actually went into the kind of folkloric sort of soup like J.R.R. Tolkien talks about in his essay on fairy tales, where the individual elements can sometimes be hard to distinguish, and it is not clear which came first.

Bernstein also talks about a lot about how scriptive things complicate the boundaries between people, creating intersubjectivity, and how slavery blurs the boundaries between people and things. In both cases, it is narrative that creates these blurred distinctions. An example of the first kind of blurred boundary is Stowe’s goal of producing “sentimental wounds” (102) in her readers as they experienced the pain of her characters. I am also interested in how narrative attempts to redefine the boundaries of the human, and how these narratives might be linked to authors’ senses of themselves as writers of autonomous or interconnected works.

Nesbit, for instance is a writer of famously intertextual works, frequently referencing periodicals, fairy tales, the work of contemporary writers for children and adults, and even her own work. I agree with Marah Gubar that Nesbit’s intertextuality was, at least in part, a strategy for improving children’s critical reading skills and making them into collaborators. However, I also see this strategy as a means of theorizing a more radical lack of separation between texts, which she then makes into an analogue for the mutual influence existing between (adult) writer and (child) reader. Moreover, she constructs the self as always both child and adult, both writer and reader, and therefore, as radically intersubjective. In Nesbit’s works, she frequently figures this intersubjectivity overtly via magic. In The Enchanted Castle, Nesbit has children, adults, and stone statues all share a moment of transcendence, and in The Story of the Amulet, Rekh-Mara and the scholar physically and psychically merge to become one person. Because issues of the relationship of writers to their audiences, and the boundaries between the two are so crucial to children’s literature, I am hoping that making this a piece of the larger project I am working on will give me some leverage with which to approach the issue in my other chapters.